Hospitality

Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) like Booking.com and Expedia helped put Iceland on the global tourism map. For many hotels, especially during the tourism boom years, they felt like a miracle button: “turn on” a listing, and international guests arrive.

But in 2025, Icelandic hotels are paying a much higher price than a simple commission line on an invoice.

In a high-cost, seasonal, geographically unique market like Iceland, heavy OTA dependence is not just “normal distribution” — it’s a structural risk to profitability, resilience, and long-term brand value.

Below is a breakdown of the key problems and what smart Icelandic hotels are doing to escape the trap.

1. The commission squeeze in a high-cost country

Iceland is already one of the most expensive countries in the world to operate a hotel:

• High wages and labour costs

• Expensive food and supplies

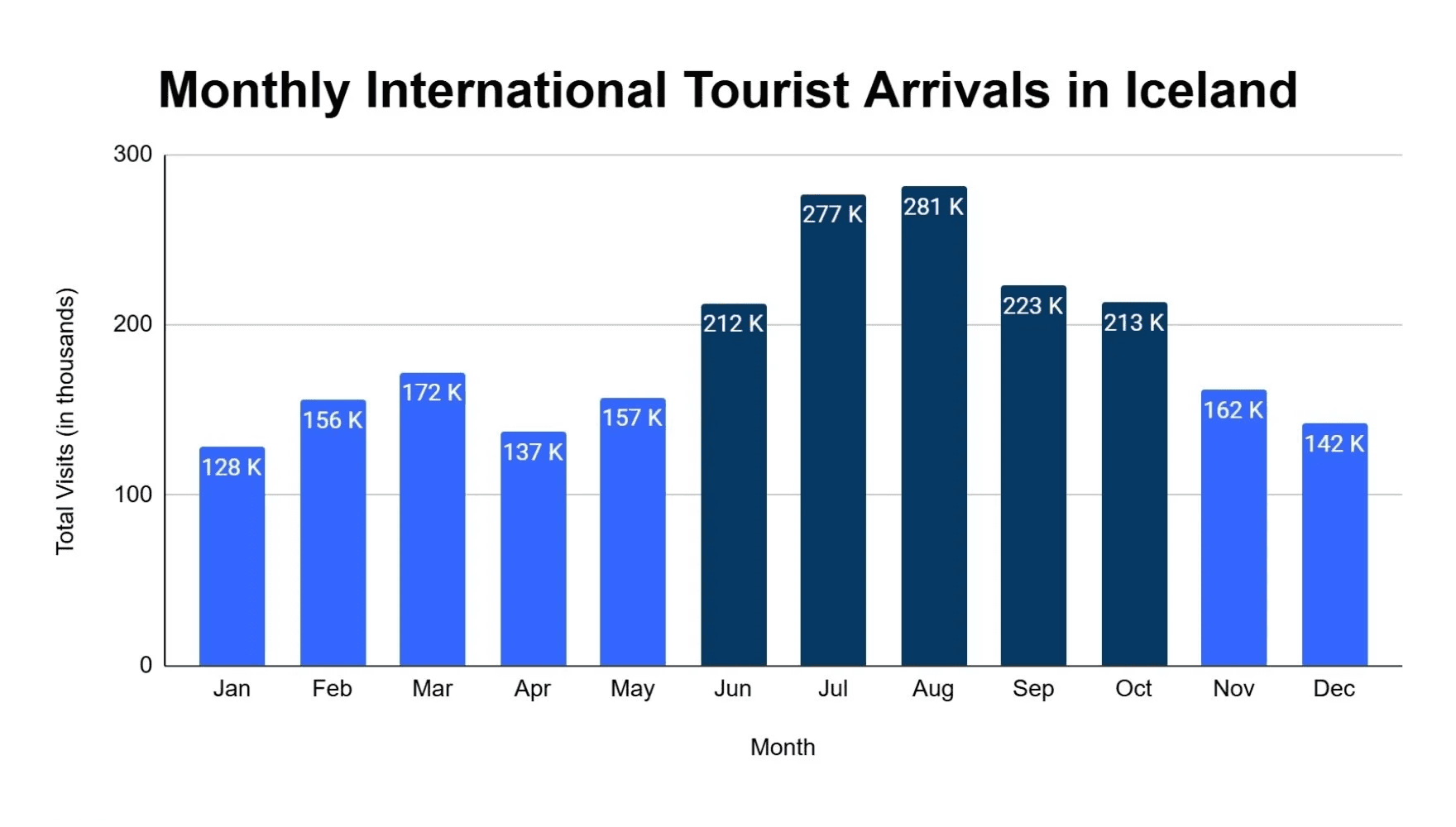

• Seasonal demand with long low periods outside peak months

On top of that, OTAs typically charge 15–30% commission per booking.

That means:

• A room that sells for €250 might net only €175–210 before your own costs.

• In many cases, most of the actual profit from a stay is transferred to the platform, not the property.

And commission is only the visible part. There are also:

• “Preferred” and “Genius” programmes that require extra discounts or higher commission for visibility.

• Promotions and offers guests now expect year-round, not just in low season.

• Operational costs of managing multiple extranets, availability, content, restrictions and overbookings.

For a Reykjavik chain with scale and brand, this is painful but manageable. For a 20–40-room countryside property, it can be existential.

2. How dependence on Booking.com became the default

Iceland’s 2015–2019 tourism boom created a dependency trap:

• Visitor numbers grew much faster than local digital infrastructure.

• New hotels and guesthouses joined OTAs with little negotiation, just to “not miss the wave”.

• Many properties never invested in strong websites, direct booking engines, or metasearch presence — because OTAs were filling the rooms anyway.

The result: a large part of Iceland’s hotel inventory runs through a handful of global platforms that:

• Control visibility

• Control demand flows

• Control how guests compare and choose properties

When 60–80% of your bookings come from OTAs, commission is not “a marketing cost”. It’s a structural dependency on a foreign intermediary with different incentives.

3. Why small and rural hotels suffer the most

Family-run guesthouses, farm stays and small countryside hotels carry the heaviest weight:

• They can’t negotiate better terms like big city hotels or international chains.

• They often lack in-house marketing, revenue management, or digital specialists.

• They have fewer alternative demand channels if an OTA ranking suddenly drops.

On top of this, rural hotels face very specific disadvantages:

• Algorithmic visibility: Reykjavik and “Instagram-famous” regions are pushed first in search results, while mid-country or remote properties are buried deeper.

• Long driving distances: a last-minute cancellation in the countryside is much harder to resell than a city room.

• Seasonality: a lost booking in shoulder season or winter may simply never be replaced.

In other words, the hotels least able to absorb shocks are the ones most exposed to OTA risk.

4. OTAs distort Iceland’s tourism map

Iceland’s tourism brand is built on authenticity: real landscapes, real villages, real family-run stays.

OTA platforms don’t care about that. They care about:

• Conversion rate

• Average daily rate

• Cancellation flexibility

• Click-through from search results

So they reduce unique properties to a spreadsheet of:

• Price per night

• Star rating

• Distance from a landmark

• Cancellation policy

• A few standardised amenity icons

This has consequences:

• Guests often choose based on price and review score, not on the story or identity of the place.

• Regions that are easier to “sell” algorithmically get disproportionate visibility.

• Slower, more authentic areas stay invisible unless hotels pay more or sacrifice margin.

The result is a tourism pattern driven by platform logic, not by what’s best for Iceland or for local communities.

5. The invisible cost: loss of control over pricing, guests & data

For years, rate-parity clauses and “best price” expectations meant hotels could not simply put a cheaper rate on their own website than on Booking.com.

Even now, with parity clauses being challenged or banned in many European markets, the habits remain:

• Guests start their search on OTAs because they believe “the best price is always there”.

• Wholesalers and secondary OTAs sometimes undercut the hotel’s own site using leaked net rates.

• Many hotels still mirror OTA prices on their website instead of using direct-only advantages.

At the same time, hotels lose ownership of the guest relationship:

• Communication goes through OTA messaging systems.

• Email addresses are hidden or anonymised.

• Building a real loyalty programme or mailing list becomes harder.

• On the next trip, guests go back to Booking.com — not to your brand.

Hotels are also locked out of the most valuable asset of all: Data.

OTAs know:

• Who is searching for Iceland

• Which dates and regions are heating up

• Which segments convert best at which price

You only see your own little slice of the puzzle.

6. Seasonality + free cancellations = revenue volatility

OTAs aggressively promote free cancellation and ultra-flexible policies because it boosts conversions on their platforms.

For Icelandic hotels this creates a perfect storm:

• High season dates fill up early with “maybe” bookings.

• Guests re-book when they find a slightly cheaper or more “Instagrammable” option.

• Rooms can drop back into inventory very late — sometimes too late to resell, especially in remote areas.

So even when your calendar looks full, your revenue is not truly secure. This adds stress to cashflow planning and staff scheduling and makes an already volatile business even more fragile.

7. Regulation and technology are finally on your side

The good news: the landscape is changing in favour of hotels.

Across Europe, including Iceland, competition authorities and courts have pushed back against the most restrictive OTA practices:

• Wide rate-parity clauses have been banned or limited in many jurisdictions.

• Hotels can increasingly offer better deals on their own channels — lower rates, better cancellation, or added value (late checkout, upgrades, packages).

At the same time, the technology required to build a strong direct channel is no longer reserved for big chains:

• Fast, mobile-first websites that actually convert

• Modern booking engines with upsells, add-ons and clear UX

• Google Hotel Ads and metasearch to put your own website next to OTAs in search results

• Simple CRM and email automation to keep in touch with past guests

Case studies from Europe show hotels growing direct bookings by 150–250% in 1–3 years when they commit to a real direct-first strategy, while reducing OTA share — not by “switching off Booking.com”, but by rebalancing the mix.

8. What successful Icelandic hotels do differently

The hotels that are quietly winning back control tend to follow a similar playbook:

1. Treat OTAs as a channel, not as the business

They define a target mix (for example, 40–50% direct, 30–40% OTA, the rest corporate/agents) and manage towards it.

2. Invest in a serious website and booking engine

Not just a brochure site, but a fast, multilingual, mobile-optimised site with a frictionless booking flow and clear value for booking direct.

3. Use pricing freedom intelligently

They offer:

• Slightly better rates on direct channels, or

• The same rate but with better cancellation, breakfast included, or added experiences.

4. Build and use their own guest database

They encourage direct contact, capture emails (with consent), and send relevant, seasonal offers instead of letting OTAs “own” repeat business.

5. Optimise where guests actually search

They appear on Google Hotel Ads, Maps and metasearch with their own booking link, so guests who discover the hotel via Google don’t immediately leak to OTAs.

6. Monitor commissions like a core cost

They track OTA commission as carefully as they track payroll or utilities — and actively move demand from the most expensive channels to more efficient ones.

9. From OTA hostage to healthy distribution mix

The problem in Iceland is not that Booking.com exists. The problem is over-reliance:

• Too many hotels let OTAs decide who their guests are, how they find them, and how much margin is left at the end of the month.

• Too few owners see OTA dependence as a strategic risk on the same level as interest rates, staffing, or energy costs.

The solution is not to declare war on OTAs. It’s to:

• Regain control of your pricing and positioning

• Build a serious direct booking ecosystem

• Use OTAs as one of several channels — not the master switch for your occupancy

If you’re an Icelandic hotel owner and your gut feeling is that “Booking takes too much, but I don’t know how to reduce it without killing my occupancy,” you’re exactly the kind of property that can benefit the most from a structured, data-driven direct-first strategy.